Wang Chunjiang’s “Hazy Summer Rain” series cuts through the surface of modern life with the blade of poetry, revealing a life wisdom that hovers between knowing and unknowing. These works are not only a dance of words, but also an extension of his ink painting spirit—through his creative philosophy of “probing forms, seeking meaning, weaving patterns,” he again uses poetic brushstrokes to outline the survival truths often neglected by the senses.

1. The Realm of Ambiguity: Wisdom Dwells in the “Half-Clear”

“Hazy Summer Rain” begins with a declaration: “Half knowing, half not knowing / Half clear, half obscure / Half recognizing, half unrecognizing / Better than being crystal clear.” This praise for ambiguity echoes Wang’s aesthetic pursuit of “neither ancient nor modern, yet both at once.” With an anti-common-sense stance, the poet questions the modern obsession with omniscience. In “Spiritual Intellect”, he elevates this stance into a survival strategy: the soul of wisdom deliberately “shuts down certain conventional senses” to resist the flood of information.

This restraint parallels the blank space technique in ink painting. While modern individuals “open all their senses to seize every possible advantage,” the poet, like his Daoist figures, preserves clarity of soul in a state of “serene simplicity and quiet grace.”

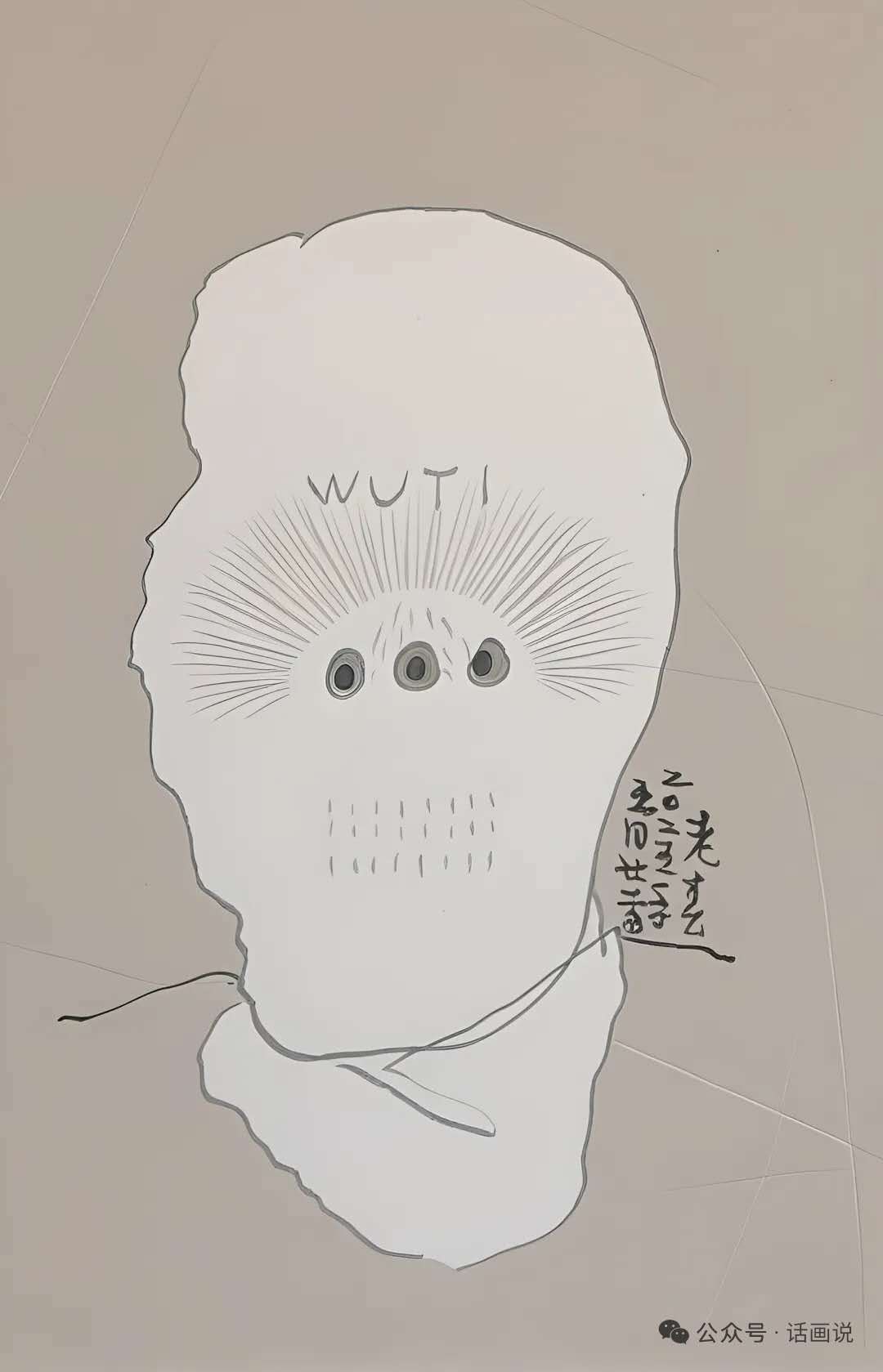

2. The Web of Power: Disciplined Bodies and Distorted Faces

Lurking in the poems is a sharp social scalpel. “Hierarchy” exposes the harsh truth behind natural order: “The top and the bottom” are but “a sociological division of status and rank.” Power structures’ discipline of the individual is embodied in “Euphemism”, where the body becomes the narrative: “A supple posture is trained through constant bowing and bending.”

Even more unsettling is the metaphor in “Face”: “Some faces change too fast / So they have no fixed features.” This stands in dramatic contrast to the “gentle and honest” expressions in Wang’s ink portraits, pointing to the fragmentation of modern identity and calling forth the unconditioned authenticity within.

3. Moments of Glimmer: Salvaging the Eternal from Dust

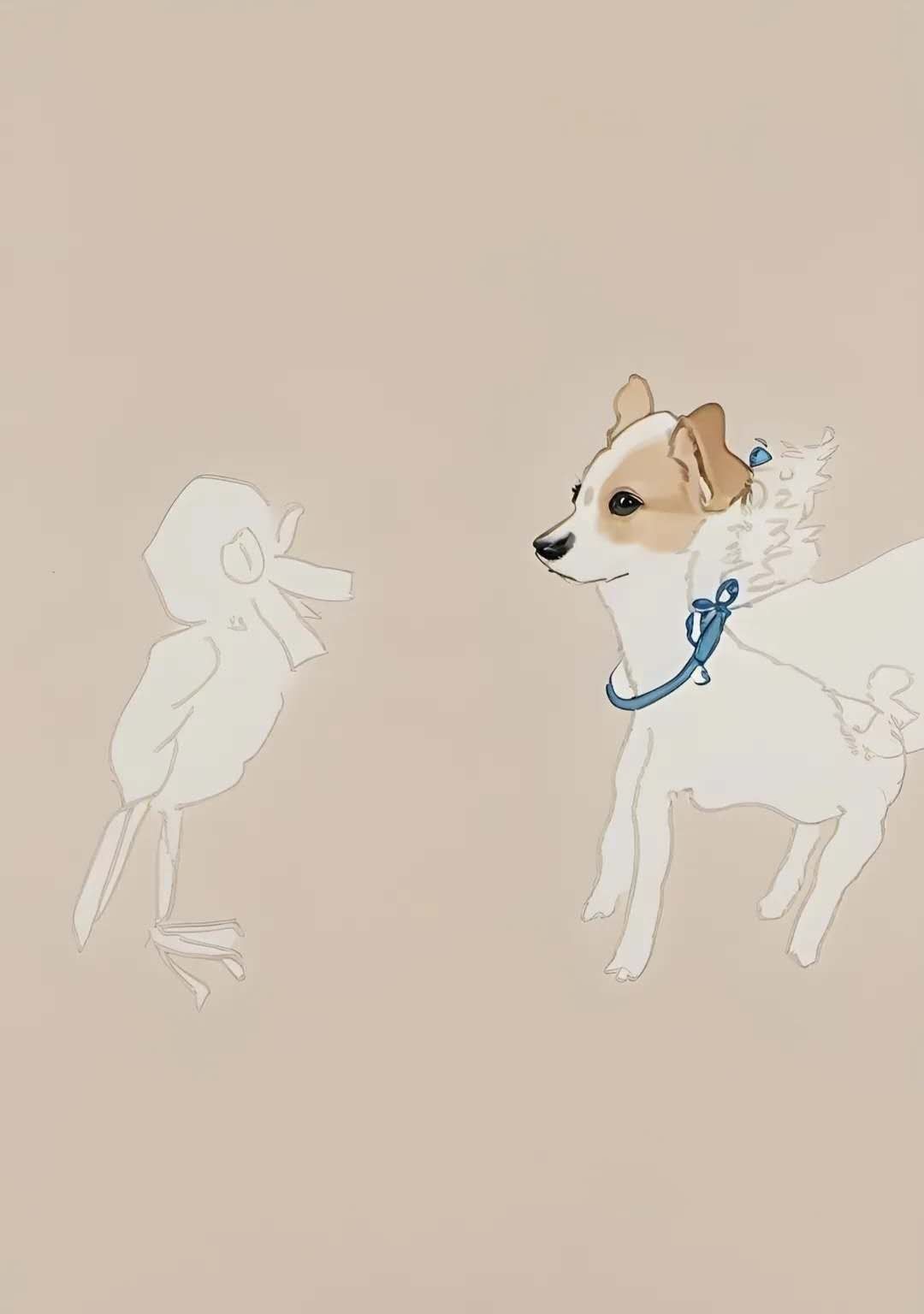

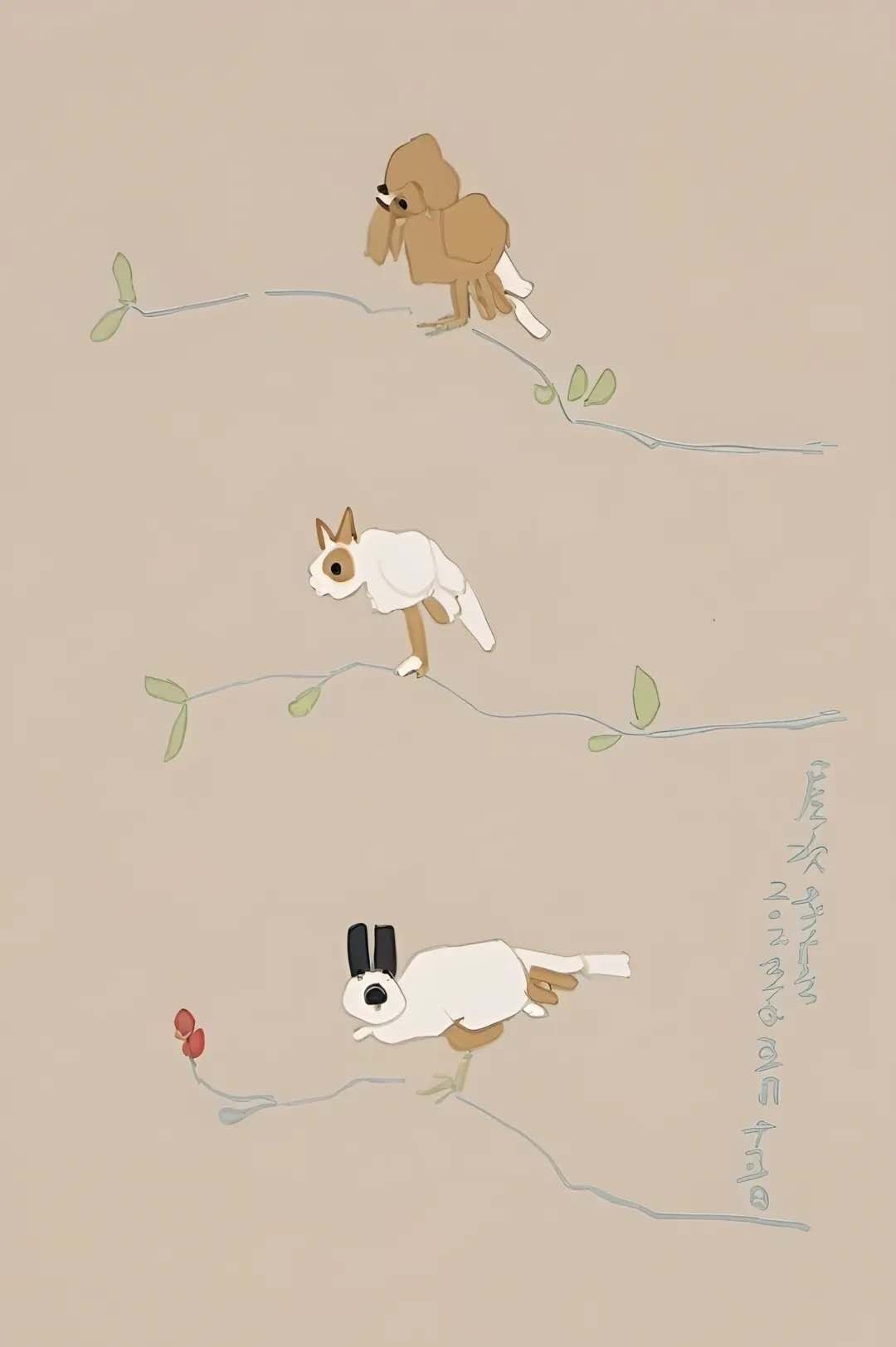

Wang excels at discovering divinity in the mundane, just as his paintings often find aesthetic charm in overlooked subjects. In “Back-Pounding”, the “insignificant dusk” is elevated into a life-scape; “Vase Flowers” reveals a chance encounter in life with “a brilliant return for a fleeting glance”; “Frost Flowers” constructs three aesthetic dimensions—from “visible and tangible” to “invisible and unreachable”—capturing the transient and precious beauty of the human world.

These moments, endowed with divinity, reflect the transformation of the ordinary into the sublime—like the inscription on his painting: “Even foot-soaking and itch-scratching are literary subjects.” While “Driving the Carriage” laments women’s “toiling into nagging matrons,” it is in the silhouette of back-pounding that eternity is glimpsed. This tension embodies the poet’s deepest compassion for the secular world.

4. The Ethics of Silence: When Gazing Becomes a Moral Choice

The poetry constructs a unique sensory ethics. “Staring Eyes” states: “An unintentional glance and a focused stare / Are two different moralities,” criticizing today’s culture of overexposure and voyeurism. Meanwhile, “Not Speaking offers a life maxim: “Keep the beauty in your heart / Don’t speak the mystery aloud”—resonating with his painting philosophy of “seeking spirit, not likeness.”

This restraint crystallizes in “Beauty” as a code of being:

“Though the mist is thin tonight / The moonlight is just right / The heart feels very tangled.”

The three uses of “just right” intensify the ineffable mood, anchoring it in the hazy moonlight and embodying his “word-brewing and character-forging” alchemy of language.

Wang Chunjiang’s poetry shares the same soul as his ink figure paintings: whether it is the metaphor between ”Necklace“ and collar, or the heritage of “the nation rests in the heart” in ”Father and Son“, he upholds the authenticity of life untainted by instrumental rationality with an attitude of “guarding clumsiness and seeking wonder.” These poems, like his figures—“simple and awkward, yet full of secret wit”—persist with the silent strength of restraint in an age of noise. While the world scrambles to light every sensory beacon, the true sage retains a pair of contemplative eyes for the moonlight in the haze of ”Hazy Summer Rain“.